BMJ:精神分裂症真的并不存在?

2016-02-14 生物谷 生物谷

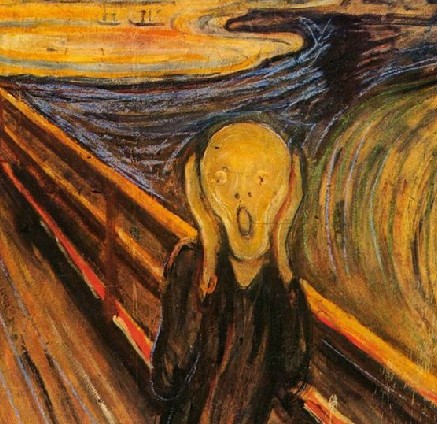

图片来自 Kim J, Matthews NL, Park S./PLoS ONE。 术语“精神分裂症(schizophrenia)”暗示着医治不好的慢性脑部疾病。在一篇发表在BMJ期刊上的论文中,荷兰马斯特里赫特大学医学中心精神病学教授Jim van Os声称,人们应当停止使用这一术语,而使用诸如“精神疾病谱系综合征(psychosis spectrum syndrome)”之类的概念代替

图片来自 Kim J, Matthews NL, Park S./PLoS ONE。

van Os教授说,已有其他几位科学家要求更新现有的精神疾病分类,特别是术语“精神分裂症”。日本和韩国已放弃使用这一术语。

医生们用来诊断病人的官方精神疾病分类见于ICD-10(第10版国际疾病分类)和DSM-5(第五版精神疾病诊断与统计手册)中。

但是van Os教授声称这种分类比较复杂,尤其是对精神疾病(psychotic illness)。

他解释道,当前,精神疾病可分为很多类型,如精神分裂症、情感分裂性精神障碍(schizoaffective disorder)、妄想性障碍、抑郁症或伴随精神疾病症状的躁郁症,以及其他。

但是,诸如这些的类型“并不代表着不相关联的疾病的诊断结果,这是因为这些疾病人们并不了解,不过,它们描述着如何能够对症状进行归类,从而允许对病人进行分组。”

比如,这允许临床医生说道,“你有精神错乱和狂躁的症状,我们因此将它归类为情感分裂性精神障碍。如果你的精神疾病症状消失,我们可能重新将它归类为躁郁症。另一方面,如果你的狂躁症状消失,但是你的精神错乱变成慢性的,我们可能将它重新诊断为精神分裂症。”

“这就是我们目前的分类系统的工作方式。我们并不知道得足够多来诊断真实的疾病,因此我们使用一种基于症状的分类系统。”

他说,如果每个人同意以这种方式使用ICD10和DSM-5中的术语,这不会有问题。但是,实际上并不是这种情形,特别是针对精神疾病中最为重要的一个类型:精神分裂症。

比如,发布DSM分类的美国精神病学协会在其网站上将精神分裂症描述为“一种慢性的脑部功能障碍”,而学术期刊将它描述为一种“衰弱性的神经障碍”,一种“破坏性的高度遗传性的脑部功能障碍”,或者一种“主要是由遗传风险因子导致的脑部功能障碍”。

van Os写道,这种语言描述高度提示着它是一种独特的遗传性脑部疾病。然而奇怪的是,在占精神疾病70%的其他类型精神疾病中,还未见到这样的描述。

他补充道,科学证据表明不同类型的精神疾病可被视为同一种谱系综合征的一部分。但是,患上这种精神疾病谱系综合征的病人在不同人群之间和在同一人群内表现出异常的精神病学、治疗反应和治疗结果上的多样性。

他认为告诉公共和提供病人诊断结果的最好方式是忘记“破坏性很大的”精神分裂症,而且这个分类之所以重要是因为“它开始让人们知道这个范围宽广的多样化的精神疾病谱系综合征确实存在。

他声称第11版国际疾病分类(ICD-11)应当移除“精神分裂症”这一术语。

Jim van Os, “Schizophrenia” does exist. BMJ 2016; 352 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i375

本网站所有内容来源注明为“梅斯医学”或“MedSci原创”的文字、图片和音视频资料,版权均属于梅斯医学所有。非经授权,任何媒体、网站或个人不得转载,授权转载时须注明来源为“梅斯医学”。其它来源的文章系转载文章,或“梅斯号”自媒体发布的文章,仅系出于传递更多信息之目的,本站仅负责审核内容合规,其内容不代表本站立场,本站不负责内容的准确性和版权。如果存在侵权、或不希望被转载的媒体或个人可与我们联系,我们将立即进行删除处理。

在此留言

#BMJ#

56

#精神分裂#

56

Richard Saville-Smith的评价:

I'm familiar with Jim van Os' work and find it of value in its contributions to questions beyond the day to day clinical issues which routinely dominate psychiatrists. For example, I find the arguments advanced by Burns, Crow, Horrobin and Nichols about the evolutionary basis of schizophrenia both fascinating and frustrating.

Fascinating in their inevitable conclusion that the schizophrenic are part of the neurodiversity (or whole body diversity as Horrobin would have it) of being human, frustrating because it is patently obvious that schizophrenia is an anachronistic concept when applied to pre-sub-Saharan diaspora of Homo Erectus/Sapiens. Schizophrenia didn't exist before Bleuler. The result is that as the scholars mentioned have overly privileged schizophrenia, the wider evolutionary contribution of the genetic propensity for psychosis is squeezed out of the discussion.

Jim van Os' approach provides a bigger, richer fuller idea of madness with a contribution to human development which is multi-dimensional not just 'bad'. This not only deconstructs the urge to pathologize madness (the inevitable consequence of focusing on the negatives and casting them in terms of mental illness) but loosen up the nosological propensity to confuse naming with understanding.

In an evolutionary context where madness is not mental illness and we are not always driven by the relentless negativity conjured by schizophrenia, the evolutionary advantages of psychosis to the human population can be considered in ways which are less bleak and more fecund .

Thanks Jim!

Burns, Jonathan Kenneth. "An Evolutionary Theory of Schizophrenia: Cortical Connectivity, Metarepresentation, and the Social Brain." Behavioral and Brain Sciences 27, no. 6 (2004): 831-55.

Crow, Timothy. "Aetiology of Schizophrenia", Current Opinion in Psychiatry 7, no. 1 (1994): 39-42. (and similar)

Horrobin, David F. The Madness of Adam and Eve : How Schizophrenia Shaped Humanity. London: Corgi, 2002.

Nichols, Catherine. "Is There an Evolutionary Advantage of Schizophrenia?" Personality and Individual Differences 46, no. 8 (2009): 832-38.

169

Stephen M Lawrie的评价:

Re: “Schizophrenia” does not exist

To state that schizophrenia does not exist is a trite assertion with no more meaning than saying, for example, that migraine does not exist. It would be equally meaningless to suggest that any abstract noun or concept does or does not exist. The key question is whether it is a useful concept, and even this may have to be asked within a defined context. (1)

The use of the term schizophrenia has allowed us to identify genes that increase risk, reproducible biological concomitants and, most importantly, treatments that are known to work from the results of clinical trials. (2-4) While schizophrenia has often been misrepresented, there is no strong evidence that doing away with the term is the solution. The ideas that schizophrenia always has a poor outcome and for which treatment at best ameliorative are just plain wrong. (5) Equally, however, we have to accept that about one-third of people with schizophrenia have a poor outcome. Changing the name of their condition won’t do anything to help those people. And to move towards having different terms around the world would be a retrograde step. It would be much preferable and more achievable to communicate more accurately about schizophrenia.

It would also be wrong to think no useful research is done on other psychosis categories. We know, for example, that most people with a brief psychotic disorder do not need ongoing treatment, (6,7) and that patients with bipolar disorder tend to respond to lithium, whereas those with schizophrenia do not. (8,9) Doing away with these diagnostic terms would simultaneously dispense with decades of clinical experience and research endeavour.(8) And for what? Because one of a number of vague alternatives may have a chance of reducing stigma? And what about the potential harms of such a conceptual change? To move to the less well defined runs the risk of increasing mis-diagnosis and losing what we already know about how to help patients in clinical settings.

The correct response to the heterogeneity of schizophrenia and the even greater heterogeneity of ‘psychosis’ is to study and to seek to progressively sub-group, building on accumulated wisdom. (9) This demands painstaking research. Just because a word like schizophrenia is mis-used does not mean it should be abandoned; and replacing it with something else of unproven value is likely to do more harm than good.

153

Iris E Sommer的评价:

Schizophrenia: Change the Name and Broaden the Concept?

In his opinion paper, van Os posits that:

1. Schizophrenia is a heterogeneous syndrome, not a specific disease;

2. Expert opinions, diagnostic manuals, and clinicians cause patients to wrongly believe they have a devastating genetic illness;

3. Forming a single category “Psychosis Susceptibility Syndrome” including schizophrenia with a number of other psychosis categories will increase knowledge of understudied categories, while providing better information for persons with psychotic disorders.

4. Removing the term “schizophrenia” would reduce the effect of stigma.

We respond to his opinion on these four points below.

Point 1: We agree that schizophrenia (and most other psychotic disorders) are heterogeneous clinical syndromes but disagree on aspects of his critique and proposed solution. In order to come to individualized treatment, it will be key to explore underlying factors. In this way, the DSM-5 category is a starting point, not an endpoint.

Point 2: Van Os believes that diagnostic manuals such as DSM-5 reinforce a false view of schizophrenia as a devastating genetic disorder. We share the concern that professional and public perception often ignores the extensive data documenting a wide variety of courses including very good outcome in perhaps 20% of persons with schizophrenia. However, it should be noted that DSM-5 gives very specific emphasis to the syndromal status of psychotic disorders, provides symptom dimensions giving emphasis on what doctors need to know about patients, and that therapeutic targets lie beyond diagnostic categories.

Doctors and patients need to develop a shared view of illness and psychosis is no exception. Physicians are not entitled to withhold relevant information from patients. To inform a person with schizophrenia that they have a devastating genetic disorder would be harmful and misinformed. To withhold information on the chance for poor outcome would also be unethical. To explain to a person that many genes make small contributions to risk and that some 60-70% of variance is at the genetic level, but that these genes are also common in the population, provides a basis for discussion, not a pronouncement about the individual’s future.

The prognosis of schizophrenia can be devastating, but can also be rather good, as witnessed in many longitudinal course studies. Clinicians tend to see the latter group much less frequently than the first and may be inclined to give a too gloomy picture of expected outcome. Although Kraepelin’s original formulation viewed poor prognosis as central to dementia praecox, long-term follow-up studies have always demonstrated heterogeneity of course including good outcome. A very early example is the 40 years follow-up study that Manfred Bleuler performed of his father’s (Eugen Bleuler) patients. Registry and cohort studies show unbiased information about long-term mortality, employment rates and generally replicate good prognosis of a small, but significant, group across the globe (Holla et al. 2015; Yuen et al. 2014, Davidson et al. 2015). Most experts are well aware of these studies and report correctly on their findings to colleagues and patients. Perhaps some clinicians and the general public need to be better informed by these data and this is a challenge for public and professional education. More emphasis on remission and recovery may be needed, but it is certainly not established that clinicians routinely over-emphasize potential dire consequences of schizophrenia. In any case, prognosis assessment approaches have been available for over 60 years to assist clinicians and to inform patients that diagnosis is not fate.

Point 3. van Os’ suggestion that different categories of psychotic disorders, regardless of name, should be removed in favor of a single category comprising multiple psychoses diagnoses raises important problems. “Psychosis susceptibility syndrome” would increase the number of cases three to four fold resulting in between patient variability and within category heterogeneity that would challenge application of existing knowledge and confound future research with the problem already undermining less heterogeneous categories. In addition, there is meaningful validity to the current diagnostic categories. For example, lithium can be particularly beneficial in bipolar disorder, antipsychotic medication reduces relapse rates for most persons with schizophrenia, a schizoaffective disorder calls for explicit attention to mood disturbance as well as to psychotic symptoms, and brief psychotic disorders identify patients where long-term antipsychotic drug therapy is not indicated. To combine these various disorders in one group of “psychosis susceptibility disorder” will very substantially increases heterogeneity and confound interpretation of science at the level of clinical application.

Point 4. We agree that the proposed new name “psychosis susceptibility syndrome” has a more pleasant ring than current diagnostic terms. Changing the name is quite a rigorous way to improve the public’s and clinicians ideas about a disorder. A serious consideration of name change should be done with care, and not ad hoc. Preferably by the WHO, which can convene relevant experts and stakeholders and make a single decision with international implications rather than each country having their own nosology or name. Changing the word “schizophrenia” for a new term could be done without losing accumulated knowledge or changing future directions of clinical care or research. However, we do not know whether this would decrease stigma or make communication about the diagnostic category more informative. In Japan the translation of schizophrenia resulted in a very negative term and it was hoped that the name change would result in a more benign public perception. However, a recent report suggests that changing the new name in Japan has not appreciably changed public perception as represented in the media (Koike et al. 2015). The process of change has started at the single nation level and we believe it should quickly be addressed as an international issue. Yet the question here remains: will renaming be helpful?

To conclude: heterogeneity amongst people diagnosed with schizophrenia-related syndromes is high and this complicates individual treatment and research into new treatment strategies. The suggested even broader term “psychosis susceptibility syndrome” will make this problem even worse. If clinicians are insufficiently aware of this heterogeneity and if they provide too gloomy prognostic information, education is needed. However, it should first be investigated if this is indeed the case. Finally, whether a name change will improve stigma is not known.

130